1. Introduction¶

A central goal of biological science is to quantitatively understand how genotype influences phenotype. However, despite decades of research, a growing wealth of experimental data, and extensive knowledge of individual molecules and individual pathways, we still do not understand how biological behavior emerges from the molecular level. For example, we do not understand how transcription factors, non-coding RNA, localization signals, degradation tags, and other regulatory systems interact to control protein expression.

Consequently, physicians still cannot interpret the pathophysiological consequences of genetic variation and bioengineers still cannot rationally design microorganisms. Instead, patients often have to try multiple drugs to find a single effective drug, which exposes patients to unnecessary drugs, prolongs disease, and increases costs. Similarly, bioengineers often have to rely on time-consuming and expensive trial and error methods such as directed evolution [4][5].

Many engineering fields use mechanistic models to help understand and design complex systems such as cars [6], buildings [7], and transportation networks [8]. In particular, mechanistic models can help researchers conduct experiments with complete control, precision, and reproducibility.

To comprehensively understand cells, we must develop whole-cell (WC) computational models that predict cellular behavior by representing all of the biochemical activity inside cells [9][10][11][12]. WC models could accelerate biological science by helping researchers unify our knowledge of cell biology, identify gaps in our understanding, and conduct complex experiments that would be infeasible in vitro. WC models could also help bioengineers design microorganisms and help physicians personalize medicine.

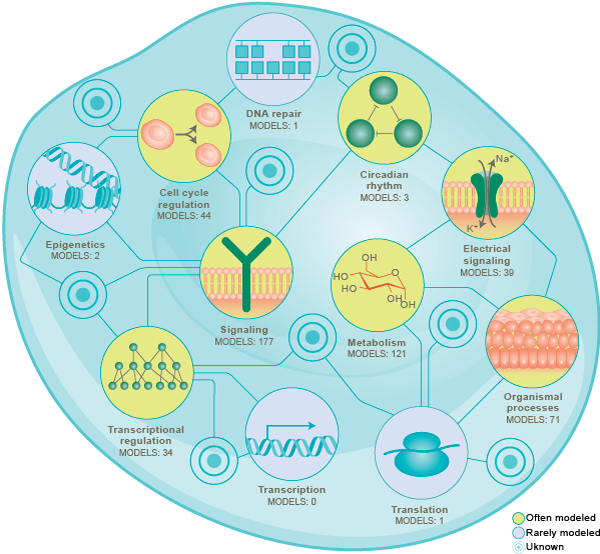

Since the 1950’s, researchers have been using modeling to understand cells. This has led to numerous models of individual pathways, including models of cell cycle regulation, chemical and electrical signaling, circadian rhythms, metabolism, and transcriptional regulation. Collectively, these efforts have used a wide range of mathematical formalisms including Boolean networks, flux balance analysis (FBA) [13][14][15], ordinary differential equations (ODEs), partial differential equations (PDEs), and stochastic simulation [16].

Over the last 20 years, researchers have begun to build more comprehensive models that represent multiple pathways [17][18][19][20][21][22][23]. Many of these models have built by combining multiple mathematically-dissimilar submodels of individual pathways into a single multi-algorithmic model [24][3].

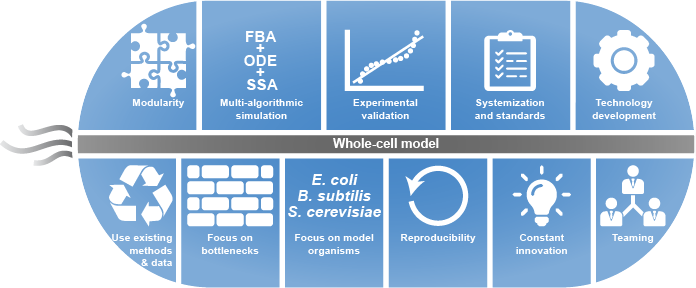

Although we do not yet have all of the data and methods needed to model entire cells, we believe that WC models are rapidly becoming feasible due to ongoing advances in measurement and computational technology. In particular, we now have a wide array of experimental methods for characterizing cells, numerous repositories which contain much of the data needed for WC modeling, and a variety of tools for extrapolating experimental data to other organisms and conditions. In addition, we now have a wide range of modeling and simulation tools, including tools for designing models, rule-based model formats for describing complex models, and tools for simulating multi-algorithmic models. However, few of these resources support the scale required for WC modeling, and many these resources remain siloed.

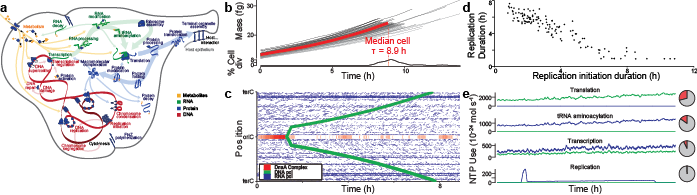

Nevertheless, we and others are beginning to model entire cells [17][25][26][27][28]. In 2012, we and others reported the first dynamical model that represents all of the characterized genes in a cell [27]. The model represents 28 pathways of the small bacterium Mycoplasma genitalium and predicts the essentiality of its genes with 80% accuracy.

However, several bottlenecks remain to build more comprehensive and more accurate WC models. In particular, we do not yet have all of the data needed for WC modeling or tools for designing, describing, or simulating WC models. To accelerate WC modeling, we must develop new methods for characterizing the single-cell dynamics of each metabolite and protein; develop new methods for scalably designing, simulating, and calibrating high-dimensional dynamical models; develop new standards for describing and verifying dynamical models; and assemble an interdisciplinary WC modeling community.

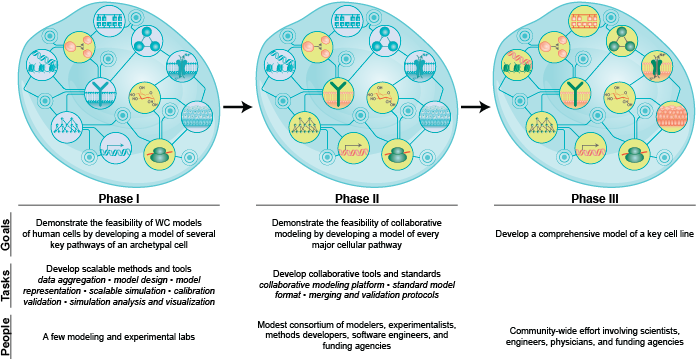

In this part, we summarize the scientific, engineering, and medical problems which are motivating WC modeling; propose the phenotypes that WC models should aim to predict and the molecular mechanisms that WC models should aim to represent; outline the fundamental challenges of WC modeling; describe why WC models are feasible by reviewing the existing methods, data, and models which could be leveraged for WC modeling; review the latest WC models and their limitations; outline the most immediate bottlenecks to WC modeling; propose a plan for achieving WC models; and summarize ongoing efforts to advance WC modeling.

1.1. Motivation for WC modeling¶

In our opinion, WC modeling is motivated by the needs to understand biology, personalize medicine, and design microorganisms. Biological science needs comprehensive models that represent the sequence, function, and interactions of each gene to help scientists holistically understanding cell biology. Similarly, precision medicine needs comprehensive models that predict phenotype from genotype to help physicians interpret the pathophysiological impact of genetic variation which can occur in any gene, and synthetic biology requires comprehensive models to help bioengineers rationally design microbial genomes for a wide range of applications.

In addition, WC models could help researchers address specific scientific problems such as determining how transcriptional regulation, non-coding RNA, and other pathways combine to regulate protein expression. Furthermore, each WC model could be used to address multiple questions, avoiding the need to build separate models for each question. However, few scientific problems require WC models, and we believe that most scientific problems would be more easily addressed with focused modeling.

Here, we describe the main applications which are motivating WC modeling. In the following sections, we define the biology that WC models must represent to support these applications and describe how to achieve such WC models.

1.1.1. Biological science: understand how genotype influences phenotype¶

Historically, the main motivation for WC modeling has been to help scientists understand how genotype and the environment determine phenotype, including how each individual gene, reaction, and pathway contributes to cellular behavior. For example, WC models could help researchers integrate heterogeneous experimental data about multiple genes and pathways. WC models could also help researchers gain novel insights into how pathways interact to control behavior. By comparison to experimental data, WC models could also help researchers identify gaps in our understanding. In addition, WC models would enable researchers to conduct experiments with complete control, infinite scope, and unlimited resolution, which would allow researchers to conduct complex experiments that would be infeasible in vitro.

1.1.2. Medicine: personalize medicine for individual genomes¶

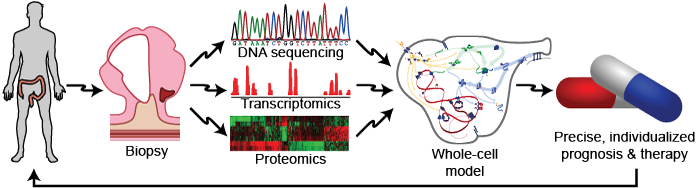

Recent studies have shown that each patient has a unique genome, that genetic variation can occur in any gene and pathway, and that small genetic differences can cause patients to respond differentially to the same drugs. Together, this suggests that medicine could be improved by tailoring therapy to each patient’s genome. Physicians are beginning to use data-driven models to tailor medicine to a small number of well-established genetic variants that have large phenotypic effects. Tailoring medicine for all genetic variation requires WC models that represent every gene and that can predict the phenotypic effect of any combination of genetic variation. Such WC models would help physicians predict the most likely prognosis for each patient and identify the best combination of drugs for each patient (Figure 1.1). For example, WC models could help oncologists conduct personalized in silico drug trials to identify the best chemotherapy regimen for each patient. Similarly, WC models could help obstetricians identify diseases in early fetuses. In addition, WC models could help pharmacologists avoid harmful gene-drug interactions.

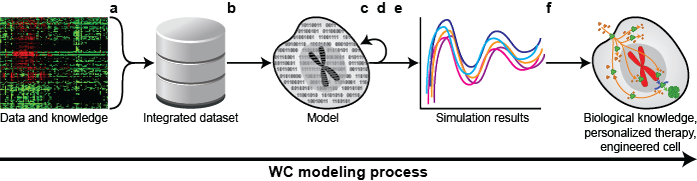

Figure 1.1 WC models could transform medicine by helping physicians use patient-specific models informed by genomic data to design personalized prognoses and therapies.¶

1.1.3. Synthetic biology: rationally design microbial genomes¶

Synthetic biology promises to create microorganisms for a wide range of industrial, medical, security applications such as cheaply producing chemicals, drugs, and fuels; quickly detecting diseased tissue; killing pathogenic bacteria; and decontaminating industrial waste. Currently, microorganisms are often engineered using directed evolution [4][5]. However, directed evolution is often time-consuming and limited to small phenotypic changes. Recently, researchers at the JCVI have begun to pioneer methods for chemically synthesizing entire genomes [29]. Realizing the full potential of this methodology requires WC models that can help bioengineers design entire genomes. For example, WC models could help bioengineers analyze the impact of synthetic circuits on host cells, design efficient chassis for synthetic circuits, and design bacterial drug delivery systems that can detect diseased tissue and synthesize drugs in situ.

1.2. The biology that WC models should aim to represent and predict¶

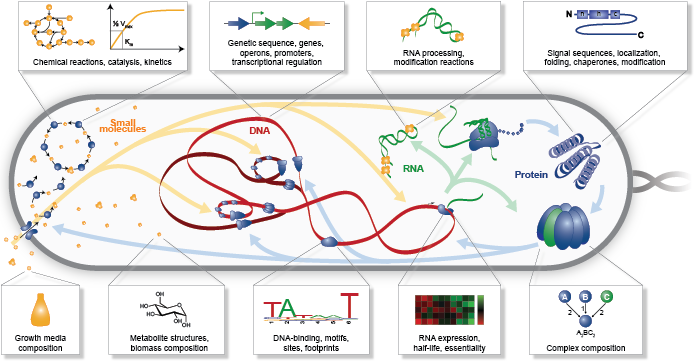

In the previous section, we argued that medicine and bioengineering need comprehensive models that can predict phenotype from genotype. Here, we outline the specific phenotypes that we believe that WC models should aim to predict and the specific physiochemical mechanisms that we believe that WC models should aim to represent to support medicine and bioengineering (Figure 1.2). In the following sections, we outline why we believe that WC models are becoming feasible and describe how to build and simulate WC models.

Figure 1.2 The physical and chemical mechanisms that WC models should aim to represent (a) and the phenotypes that WC models should aim to predict (b).¶

1.2.1. Phenotypes that WC models should aim to predict¶

To support medicine and bioengineering, we believe that WC models should aim to predict the phenotypes of individual cells over their entire life cycles (Figure 1.2b). Specifically, we believe that WC models should aim to predict the following five levels of phenotypes:

Stochastic dynamics: To help physicians understand how genetic variation affects how cells respond to drugs, and to help bioengineers design microorganisms that are robust to stochastic variation, WC models should predict the stochastic behavior of each molecular species and molecular interaction. For example, this would help physicians design drugs that are robust to variation in RNA splicing, protein modification, and protein complexation. This would also help bioengineers design feedback loops that can control the expression of key RNA and proteins.

Temporal dynamics: To help physicians understand the impact of genetic variation on cell cycle regulation, and to help bioengineers control the temporal dynamics of microorganisms, WC models should predict the temporal dynamics of the concentration of each molecular species. For example, this would help physicians identify genetic variation that can disrupt cell cycle regulation and cause cancer. This would also help bioengineers design microorganisms that can perform specific tasks at specific times.

Spatial dynamics: To help physicians predict the intracellular distribution of drugs, and to help bioengineers use space to concentrate and insulate molecular interactions, WC models should predict the concentration of each molecular species in each spatial domain. For example, this would help physicians predict whether drugs interact with their intended targets and predict how quickly cells metabolize drugs. This would also help bioengineers maximize the metabolic activity of microorganisms by co-localizing enzymes and their substrates.

Single-cell variation: To help physicians understand how drugs affect populations of heterogeneous cells, and to help bioengineers design robust microorganisms, WC models should predict the single-cell variation of cellular behavior. For example, this would help physicians understand how chemotherapies affect heterogeneous tumors, and help bioengineers design reliable biosensors that activate at the same threshold irrespective of stochastic variation in RNA and protein expression.

Complex phenotypes: To help physicians understand the impact of variation on complex phenotypes and to help bioengineers design microorganisms that can perform complex phenotypes, WC models should predict complex phenotypes such as the cell shape, growth rate, and fate. For example, this would help physicians identify the primary variants responsible for disease and help physicians screen drugs in silico. This would also help bioengineers design sophisticated strains that can detect tumors, synthesize chemotherapeutics, and deliver drugs directly to tumors.

1.2.2. Physics and chemistry that WC models should aim to represent¶

To predict these phenotypes, we believe that WC models should aim to represent all of the chemical reactions inside cells and all of the physical processes that influence their rates (Figure 1.2a). Specifically, we propose that WC models aim to represent the following seven aspects of cells:

Sequences: To predict how genotype influence phenotype, including the contribution of each individual variant and gene, WC models should represent the sequence of each chromosome, RNA, and protein; the location of each feature of each chromosome such as genes, operons, promoters, and terminators; and the location of each site of each RNA and protein.

Structures: To predict how molecular species interact and react, WC models should represent the structure of each molecule, including atom-level information about small molecules, the domains and sites of macromolecules, and the subunit composition of complexes. For example, this would enable WC models to predict the metabolism of novel compounds.

Subcellular organization: To capture the molecular interactions that occur inside cells, WC models should represent the spatial organization of cells and the localization of each of metabolite, RNA, and protein species. For example, this would enable WC models to predict the spatial compartments in which molecular interactions occur.

Concentrations: To capture the molecular interactions that can occur inside cells, WC models should also represent the concentration of each molecular species in each organelle and spatial domain.

Molecular interactions: To capture how cells behave over time, WC models should represent the participants and effect of each molecular interaction, including the molecules that are consumed, produced, and transported, the molecular sites that are modified, and the bonds that are broken and formed. For example, this would enable WC models to capture the reactions responsible for cellular growth and homeostatic maintenance.

Kinetic parameters: To predict the temporal dynamics of cell behavior, WC models should represent the kinetic parameters of each interaction such as the maximum rate of each reaction and the affinity of each enzyme for its substrates and inhibitors. For example, this would enable WC models to predict the impact of genetic variation on the function of each enzyme.

Extracellular environment: To predict how the extracellular environment, including nutrients, hormones, and drugs, influences cell behavior, WC models should represent the concentration of each species in the extracellular environment. For example, this should enable WC models to predict the minimum media required for growth.

1.3. Fundamental challenges to WC modeling¶

In the previous section, we defined the biology that WC models should represent and predict. Building WC models that represent all of the biochemical activity inside cells and that can predict any cellular phenotype is challenging because this requires integrating molecular behavior to the cellular level across several spatial and temporal scales; assembling a complete molecular understanding of cell biology from incomplete, imprecise, and heterogeneous data; and simulating, calibrating, and validating computationally-expensive, high-dimensional models. Here, we describe these challenges to WC modeling. In the following sections, we describe emerging methods for overcoming these challenges to achieve WC models.

1.3.1. Integrating molecular behavior to the cell level over several spatiotemporal scales¶

The most fundamental challenge to WC modeling is integrating the behavior of individual species and reactions to the cellular level over several spatial and temporal scales. This is challenging because it requires accurate parameter values and scalable methods for simulating large models. Here, we summarize these challenges.

1.3.1.1. Sensitivity of phenotypic predictions to molecular parameter values¶

The first challenge to integrating molecular behavior to the cellular level is the sensitivity of model predictions to the values of critical parameters, which necessitates accurate parameter values. Accurately identifying these values is challenging because, as described below, it is challenging to optimize high-dimensional functions and because, as described in Section 1.3.1, our experimental data is incomplete and imprecise.

1.3.1.2. High computational cost of simulating large fine-grained models¶

A second challenge to integrating molecular behavior to the cellular level is the high computational cost of simulating entire cells with molecular granularity. For example, simulating one cell cycle of our first WC model of the smallest known freely living organism took a full core-day of an Intel E5520 CPU, or approximately \(1 \times 10^{15}\) floating-point operations [27]. Based on this data, the fact that human cells are approximately 106 larger, and the fact that a typical WC simulation experiment will require at least 1,000 simulation runs, a typical WC simulation experiment of a human cell will require approximately 106 core-years. To simulate larger and more complex organisms, we must develop faster parallel simulators.

1.3.2. Assembling a unified molecular understanding of cells from imperfect data¶

In our opinion, the greatest challenge to WC modeling is assembling a unified molecular understanding of cell biology. As illustrated in Figure 1.3, this requires assembling comprehensive data about every molecular species and molecular interaction. For example, to model M. genitalium we reconstructed (a) its subcellular organization; (b) its chromosome sequence; (c) the location, length, direction and essentiality of each gene; (d) the organization and promoter of each transcription unit; (e) the expression and degradation rate of each RNA transcript; (f) the specific folding and maturation pathway of each RNA and protein species including the localization, N-terminal cleavage, signal sequence, prosthetic groups, disulfide bonds and chaperone interactions of each protein species; (g) the subunit composition of each macromolecular complex; (h) its genetic code; (i) the binding sites and footprint of every DNA-binding protein; (j) the structure, charge and hydrophobicity of every metabolite; (k) the stoichiometry, catalysis, coenzymes, energetics and kinetics of every chemical reaction; (l) the regulatory role of each transcription factor; (m) its chemical composition and (n) the composition of its growth medium [30].

Figure 1.3 WC models require comprehensive data about every molecular species and molecular interaction.¶

This is challenging because our data is incomplete, imprecise, heterogeneous, scattered, and poorly annotated. Here, we summarize these limitations and the challenges they present for WC modeling.

1.3.2.1. Incomplete data¶

The biggest limitation of our experimental data is that we do not have a complete experimental characterization of a cell. In particular, we have limited genome-scale data about individual metabolites and proteins, limited data about cell cycle dynamics, limited data about cell-to-cell variation, limited data about culture media, and limited data about cellular responses to genetic and environmental perturbations. Many genome-scale datasets are also incomplete. For example, most metabolomics and proteomics methods can only measure small numbers of metabolites and proteins.

1.3.2.2. Imprecise and noisy data¶

A second limitation of our experimental data is that many of our measurement methods are imprecise and noisy. For example, fluorescent microscopy cannot precisely quantitate single-cell protein abundances, single-cell RNA sequencing cannot reliably discern unexpressed RNA, and mass-spectrometry cannot reliably discern unexpressed proteins.

1.3.2.3. Heterogeneous experimental methods¶

A third limitation of our experimental data is that our data is highly heterogeneous because we do not have a single experimental technology that is capable of completely characterizing a cell. Rather, we have a wide range of methods for characterizing different aspects of cells at different scales with different levels of resolution. For example, mass-spectrometry can quantitate the concentrations of tens of metabolites, deep sequencing can quantitate the concentrations of tens of thousands RNA, and each biochemical experiment can quantitate one or a few kinetic parameters.

Consequently, our experimental data also spans a wide range of scales and units. For example, we have extensive molecular information about the participants in each metabolic reaction and their stoichiometries, but we only have limited information about the substrates of each protein chaperone. As a second example, we have extensive single-cell information about RNA expression, but we have limited single-cell data about metabolite concentrations.

1.3.2.4. Heterogeneous organisms and environmental conditions¶

A fourth limitation of our data is that we only have a small amount of data about each organism and environmental condition, and only a small amount of data from each laboratory. However, collectively, we have a large amount of data.

1.3.2.5. Siloed data¶

Another limitation of our data is that no resource contains all of the data needed for WC modeling. Rather, our data is scattered across a wide range of databases, websites, textbooks, publications, supplementary materials, and other resources. For example, ArrayExpress [31] and the Gene Expression Omnibus [32] (GEO) only contain RNA abundance data, PaxDb only contains protein abundance data [33], and SABIO-RK only contains kinetic data [34]. Furthermore, many of these data sources use different identifiers and different units.

1.3.2.6. Insufficient annotation¶

Furthermore, much of our data is insufficiently annotated to understand its biological semantic meaning and provenance. For example, few RNA-seq datasets in ArrayExpress [31] have sufficient metadata to understand the environmental condition that was measured, including the concentration of each metabolite in the growth media and the temperature and pH of the growth media. Similarly, few kinetic measurements in SABIO-RK [34] have sufficient metadata to understand the strain that was measured.

1.3.3. Selecting, calibrating and validating high-dimensional models¶

A third fundamental challenge to WC modeling is the high-dimensionality of WC models which makes WC models susceptible to the “curse of dimensionality”, the need for more data to constrain high-dimensional models [1]. In particular, the curse of dimensionality makes it challenging to select, calibrate, and validate WC models because we do not yet have sufficient data to data to select among multiple possible WC models, avoid overfitting WC models, precisely determine the value of each parameter, or test the accuracy of every possible prediction. Furthermore, it is computationally expensive to select, calibrate, and validate high-dimensional models.

1.4. Feasibility of WC models¶

Despite the numerous challenges to WC modeling described in the previous section, we believe that WC modeling is rapidly becoming feasible due to ongoing technological advances throughout computational systems biology, bioinformatics, genomics, molecular cell biology, applied mathematics, computer science, and software engineering including methods for experimentally characterizing cells, repositories for sharing data, tools for building and simulating dynamical models, models of individual pathways, and model repositories. While substantial work remains to adapt and integrate these technologies into a unified framework for WC modeling, these technologies are already forming a strong intellectual foundation for WC modeling. Here, we review the technologies that we believe are making WC modeling feasible, and describe their present limitations for WC modeling. In the following section, we describe how we are beginning to leveraging these technologies to build and simulate WC models.

1.4.1. Experimental methods, data, and repositories¶

Here, we review advances in measurement methods, data repositories, and bioinformatics tools that are generating the data needed for WC modeling, aggregating this data into repositories, and producing tools for extrapolating data to other genotypes and environments.

1.4.1.1. Measurement methods¶

Advances in biochemical, genomic, and single-cell measurement are rapidly generating the data needed for WC modeling [35][36][37] (Table 1.1). For example, Meth-Seq can assess epigenetic modifications [38], Hi-C can determine the average structure of chromosomes [39], ChIP-seq can determine protein-DNA interactions [40], fluorescence microscopy can determine protein localizations, mass-spectrometry can quantitate average metabolite concentrations, scRNA-seq [41][42] can quantitate the single-cell variation of each RNA [41], FISH [43] can quantitate the spatiotemporal dynamics and single-cell variation of the abundances of a few RNA, mass spectrometry can quantitate the average abundances of hundreds of proteins [44][45], mass cytometry can quantitate the single-cell variation of the abundances of tens of proteins [46], and fluorescence microscopy can quantitate the spatiotemporal dynamics and single-cell variation of the abundances of a few proteins. However, improved methods are still needed to measure the dynamics of the entire metabolome and proteome.

Data type |

URL |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

Metabolites |

||

Structure |

||

Mass spectrometry |

Dettmer et al., 2007 |

|

Concentration |

||

Fluorescence microscopy |

Zenobi, 2013 |

|

Mass spectrometry |

Dettmer et al., 2007 |

|

Spectrophotometry |

TeSlaa and Teitell, 2014 |

|

DNA |

||

Structure |

||

DNA sequencing |

Shendure and Ji, 2008 |

|

Methylation sequencing |

Laird, 2010 |

|

Chromosome conformation capture |

Dekker et al., 2013 |

|

Concentration |

||

Flow cytometry |

Bendall et al., 2012 |

|

RNA |

||

Structure |

||

RNA sequencing |

Ozsolak and Milos, 2011 |

|

Modification sequencing (ICE, MERIP-Seq) |

Liu and Pan, 2015 |

|

X-ray crystallography |

Reyes et al., 2009 |

|

Localization |

||

Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

Lee et al., 2014 |

|

Transcription rate |

||

ChIP-seq |

Park, 2009 |

|

GRO-seq |

Core et al., 2008 |

|

Half-life |

||

Microarray timecourse |

Selinger et al., 2003 |

|

RNA sequencing timecourse |

Schwanhäusser et al., 2011 |

|

Concentration |

||

Microarray |

Schulze and Downward, 2001 |

|

RNA sequencing |

Ozsolak and Milos, 2011 |

|

Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

Taniguchi et al., 2010 |

|

Proteins |

||

Structure |

||

Mass spectrometry |

Domon and Aebersold, 2006 |

|

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

Tugarinov et al., 2004 |

|

RNA sequencing |

Ozsolak and Milos, 2011 |

|

X-ray crystallography |

Ilari and Savino, 2008 |

|

Localization |

||

Fluorescence microscopy |

Giepmans et al., 2006 |

|

Translation rate |

||

Ribosomal profiling |

Ignolia, 2014 |

|

Half-life |

||

Fluorescence timecourse |

Knop and Edgar, 2014 |

|

Mass spectrometry timecourse |

Schwanhäusser et al., 2011 |

|

Concentration |

||

Flow cytometry |

Bendall et al., 2012 |

|

Fluorescence microscopy |

Giepmans et al., 2006 |

|

Mass cytometry |

Bendall et al., 2012 |

|

Mass spectrometry |

Domon and Aebersold, 2006 |

|

Spectrophotometery |

Noble and Bailey, 2009 |

|

Interactions |

||

RNA-DNA |

||

CHIRP-Seq |

Chu et al., 2011 |

|

Protein-metabolite |

||

Mass spectrometry |

Domon and Aebersold, 2006 |

|

Protein-DNA |

||

ChIP-seq |

Park, 2009 |

|

DNase-seq |

Song and Crawford, 2010 |

|

Protein-RNA |

||

CLIP-seq |

Darnell, 2010 |

|

RIP-seq |

Zhao et al., 2010 |

|

Protein-protein |

||

Co-immunoprecipitation |

Sambrook and Russell, 2006 |

|

Tandem affinity purification |

Xu et al., 2010 |

|

Two-hybrid screen |

Brückner et al., 2009 |

|

Reaction fluxes |

||

Isotopic labeling |

Klein and Heinzle, 2012 |

|

Phenotypic data |

||

Cell size |

||

Fluorescence microscopy |

Muzzey and van Oudenaarden, 2009 |

|

Growth rates |

||

Spectrophotometery |

Jensen et al., 2015 |

|

Division times |

||

Fluorescence microscopy |

Wang et al., 2010 |

|

Motility, chemotaxis |

||

Fluorescence microscopy |

Dormann and Weijer, 2006 |

1.4.1.2. Data repositories¶

Researchers are rapidly aggregating the experimental data needed for WC modeling into repositories (Table 1.2). This includes specialized repositories for individual types of data such as ECMDB [47] and YMDB [48] for metabolite concentrations; ArrayExpress [31] and the Gene Expression Omnibus [32] (GEO) for RNA abundances; PaxDb [33] for protein abundances; BiGG [49] for metabolic reactions, and SABIO-RK for kinetic parameters [34], as well as general purpose repositories such as FigShare [50], SimTk [51], and Zenodo [52].

Some researchers are making the data in these repositories more accessible by providing common interfaces to multiple repositories such as BioMart [53], BioServices [54], and Intermine [55].

Other researchers are making the data in these repositories more accessible by integrating the data into meta-databases. For example, KEGG contains a variety of information about metabolites, proteins, reactions, and pathways [56]; Pathway Commons contains extensive information about protein-protein interactions and pathways [57]; and UniProt contains a multitude of information about proteins [58].

In addition, some researchers are integrating information about individual organisms into PGDBs such as the BioCyc family of databases [59][60]. These databases contain a wide range of information including the stoichiometries of individual reactions, the compositions of individual protein complexes, and the genes regulated by individual transcription factors. Because PGDBs already contain integrated data about a single organism, PGDBs could readily be leveraged to build WC models. In fact, Latendresse developed MetaFlux to build constraint-based models of metabolism from EcoCyc [61].

Furthermore, meta-databases such as Nucleic Acid Research’s Database Summary [62] and re3data.org [63] contain lists of data repositories.

Most of these repositories have been developed by encouraging individual researchers to deposit their data or by employing curators to manually extract data from publications, supplementary files, and websites. In addition, researchers are beginning to use natural language processing to develop tools for automatically extracting data from publications [64].

Database |

Content |

URL |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

Species structures |

|||

Metabolites |

|||

ChEBI |

Compound structures |

Hastings et al., 2016 |

|

KEGG Compound |

Compound structures |

Kanehisa et al., 2017 |

|

KEGG Glycan |

Glycan structures |

Hashimoto et al., 2006 |

|

Metabolomics Workbench Metabolite Database |

Compound structures |

Sud et al., 2016 |

|

LIPID MAPS |

Lipid structures |

Sud et al., 2007 |

|

PubChem |

Compound structures |

Kim et al., 2016 |

|

DNA |

|||

ArrayExpress |

Functional genomics data including Hi-C data |

Kolesnikov et al., 2015 |

|

GenBank |

DNA sequences |

Benson et al., 2017 |

|

GEO |

Functional genomics data including Hi-C data |

Clough and Barrett, 2016 |

|

MethDB |

Methylation sequencing data |

Grunau et al., 2001 |

|

RNA |

|||

ArrayExpress |

Functional genomics data including RNA-seq data that encompasses initiation and termination sites |

Kolesnikov et al., 2015 |

|

GEO |

Functional genomics data including RNA-seq data that encompasses initiation and termination sites |

Clough and Barrett, 2016 |

|

MODOMICS |

Post-transcriptional modifications |

Machnicka et al., 2013 |

|

RNA Modification Database |

Post-transcriptional modifications |

Cantara et al., 2011 |

|

Protein |

|||

3d-footprint |

3-dimensional footprints |

Contreras-Moreira, 2010 |

|

dbPTM |

Post-translational modifications |

Huang et al., 2016 |

|

PDB |

3-dimensional structures |

Rose et al., 2017 |

|

RESID |

Post-translational modifications |

Garavelli, 2004 |

|

UniMod |

Post-translational modifications |

Creasy and Cottrell, 2004 |

|

UniProt |

Functional protein annotations including post-translational modifications |

The UniProt Consortium, 2017 |

|

Localization and signal sequences |

|||

RNA |

|||

Fly-FISH |

RNA localizations |

Wilk et al., 2006 |

|

RNALocate |

RNA localizations |

Zhang et al., 2017 |

|

Protein |

|||

COMPARTMENTS |

Protein localizations for Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, and Rattus norvegicus |

Binder et al., 2014 |

|

Human Protein Reference Database |

Protein localizations for Homo sapiens |

Prasad et al., 2009 |

|

LOCATE |

Protein localizations for Homo sapiens and Mus musculus |

Sprenger et al., 2008 |

|

LocDB |

Protein localizations for Arabidopsis thaliana and Homo sapiens |

Rastogi and Rost, 2011 |

|

LocSigDB |

Protein localizations for eukaryotes |

Negi et al., 2015 |

|

OrganelleDB |

Protein localizations |

Wiwatwattana et al., 2007 |

|

PSORTdb |

Protein localizations for bacteria and archaea |

Peabody et al., 2016 |

|

UniProt |

Functional protein annotations including protein localizations |

The UniProt Consortium, 2017 |

|

Concentrations |

|||

Metabolites |

|||

BioNumbers |

Quantitative measurements of physical, chemical, and biological properties including metabolite concentrations |

Milo et al., 2010 |

|

ECMBD |

Metabolite concentrations in Escherichia coli |

Sajed et al., 2016 |

|

HMDB |

Metabolite concentrations in Homo sapiens |

Wishart et al., 2013 |

|

MetaboLights |

Kale et al., 2016 |

||

YMDB |

Metabolite concentrations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

Ramirez-Gaona et al., 2017 |

|

RNA |

|||

ArrayExpress |

Functional genomics data including RNA abundances from microarray and RNA-seq experiments |

Kolesnikov et al., 2015 |

|

Expression Atlas |

RNA abundances across organisms and environmental conditions |

Petryszak et al., 2016 |

|

GEO |

Functional genomics data including RNA abundances from microarray and RNA-seq experiments |

Clough and Barrett, 2016 |

|

Proteins |

|||

Review |

Perez-Riverol et al., 2015 |

||

Human Protein Atlas |

Protein abundances for Homo sapiens |

Uhlén et al., 2015 |

|

PaxDb |

Protein abundances |

Wang et al., 2015 |

|

Plasma Proteome Database |

Protein abundances for Homo sapiens plasma |

Nanjappa et al., 2014 |

|

PRIDE |

Mass-spectrometry proteomics data |

Vizcaíno et al., 2016 |

|

Interactions |

|||

Protein-Metabolite, See also: Cofactors |

|||

Review |

Matsuda et al., 2014 |

||

DrugBank |

Drugs and their targets |

Law et al., 2014 |

|

STITCH |

Drugs and their targets |

Szklarczyk et al., 2016 |

|

SuperTarget |

Drugs and their targets |

Hecker et al., 2012 |

|

Therapeutic Targets Database |

Drugs and their targets |

Zhu et al., 2012 |

|

Protein-DNA |

|||

ArrayExpress |

Functional genomics data including ChIP-seq data of protein-DNA interations |

Kolesnikov et al., 2015 |

|

GEO |

Functional genomics data including ChIP-seq data of protein-DNA interations |

Clough and Barrett, 2016 |

|

DBD |

Predicted transcription factors |

Wilson et al., 2008 |

|

DBTBS |

Bacillus subtilis transcription factors and the operons they regulate |

Sierro et al., 2008 |

|

ORegAnno |

Transcription factor binding sites |

Lesurf et al., 2016 |

|

TRANSFAC |

Transcription factor binding motifs |

Matys et al., 2003 |

|

UniProbe |

Transcription factor binding motifs |

Hume et al., 2015 |

|

Protein-Protein |

|||

Review |

Lehne et al., 2009 |

||

ConsensusPathDB |

Homo sapiens molecular interactions including protein-protein interactions |

Kamburov et al., 2013 |

|

BioGRID |

Protein-protein interactions |

Chatr-aryamontri et al., 2017 |

|

CORUM |

Protein complex composition |

||

DIP |

Protein-protein interactions |

Salwinski et al., 2004 |

|

IntAct |

Molecular interactions including protein-protein interactions |

Szklarczyk et al., 2017 |

|

STRING |

Protein-protein interactions |

Kerrien et al., 2012 |

|

UniProt |

Function protein annotations including protein complex compositions |

The UniProt Consortium, 2017 |

|

Reactions |

|||

Stoichiometries, catalysis |

|||

BioCyc |

Reaction stoichiometries and catalysts |

Caspi et al., 2016 |

|

KEGG |

Reaction stoichiometries and catalysts |

Kanehisa et al., 2017 |

|

MACiE |

Detailed reaction mechanisms |

Holliday et al., 2012 |

|

Rhea |

Reaction stoichiometries |

Morgat et al., 2017 |

|

UniProt |

Reaction stoichiometries and catalysts |

The UniProt Consortium, 2017 |

|

Cofactors |

|||

CoFactor |

Organic enzyme cofactors |

Fischer et al., 2010 |

|

PDB |

3-dimensional protein structures including cofactors |

Rose et al., 2017 |

|

UniProt |

Functional protein annotations including cofactors |

The UniProt Consortium, 2017 |

|

Rate laws and rate constants |

|||

BioNumbers |

Quantitative measurements of physical, chemical, and biological properties including kinetic parameters |

Milo et al., 2010 |

|

BRENDA |

Kinetic parameters and rate laws |

Schomburg et al., 2017 |

|

SABIO-RK |

Kinetic parameters and rate laws |

Wittig et al., 2012 |

|

Pathways |

|||

Metabolic |

|||

Review |

Karp and Caspi, 2011 |

||

BioCyc |

Species-specific pathways |

Caspi et al., 2016 |

|

KEGG PATHWAY |

Species-specific pathways |

Kanehisa et al., 2017 |

|

Signaling |

|||

Review |

Chowdhury and Sarkar, 2015 |

||

hiPathDB |

Metadatabase of Homo sapiens signaling pathways |

Yu et al., 2012 |

|

KEGG PATHWAY |

Pathways including signaling pathways |

Kanehisa et al., 2017 |

|

NetPath |

Immune signaling pathways |

Kandasamy et al., 2010 |

|

PANTHER Pathway |

Pathways including signaling pathways |

Mi et al., 2017 |

|

Pathway Commons |

Metadatabase of signaling pathways |

Cerami et al., 2011 |

|

Reactome |

Pathways including signaling pathways |

Fabregat et al., 2016 |

|

WikiPathways |

Community curated pathways including signaling pathways |

Kutmon et al., 2016 |

|

Meta-databases and meta-database tools |

|||

Review |

Urdidiales-Nieto et al., 2017 |

||

BioCatalogue |

List of web services |

Bhagat et al., 2010 |

|

BioMart |

Tools for integrating data from multiple repositories |

Kasprzyk, 2010 |

|

BioMoby |

Ontology-based messaging system for discovering data |

BioMoby Consortium et al., 2008 |

|

BIOSERVICES |

Python APIs to several popular repositories |

Cokelaer et al., 2013 |

|

BioSWR |

List of web services |

Repchevsky and Gelpi, 2014 |

|

ELIXIR |

Effort to develop a common data infrastructure for Europe |

Crosswell and Thornton, 2012 |

|

NAR Database Summary |

List of database papers published in Nucleic Acids Research database issues |

Galperin et al., 2017 |

|

re3data.org Registry |

List of data repositories |

Pampel et al., 2013 |

1.4.1.3. Prediction tools¶

Accurate prediction tools can be a useful alternative to constraining models with direct experimental evidence. Currently, many tools can predict molecular properties such as the organization of genes into operons, RNA folds, and protein localizations (Table 1.3). For example, PSORTb can predict the localization of bacterial proteins [65] and TargetScan can predict the mRNA targets of small non-coding RNAs [66]. In particular, these tools can be used to impute missing data and extrapolate observations to other organisms, genetic conditions, and environmental conditions. However, many current prediction tools are not sufficiently accurate for WC modeling.

Tool |

Prediction(s) |

Language |

URL |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Metabolites |

||||

Physical properties |

||||

Review |

Survey of several chemoinformatic packages |

O’Boyle et al., 2011 |

||

Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) |

Java libraries for processing chemical information |

Java |

Steinbeck et al., 2006 |

|

Cinfony |

A common API to several cheminformatics toolkits |

Python |

O’Boyle and Hutchison, 2008 |

|

Indigo |

A toolkit for molecular fingerprinting, substructure searching, and visualization |

C++, Java, .Net, Python |

||

JChem |

Tools for draw and visualizing molecules and searching chemical databases |

Java, .Net, REST |

Csizmadia, 2000 |

|

Open Babel |

Tools for searching, converting, analyzing, and storing chemical structures |

C++, Java, .Net, Python |

O’Boyle et al., 2011 |

|

RDKit |

Cheminformatics toolkit |

C++, Python |

||

Thermodynamics |

||||

UManSysProp |

Estimates the standard Gibbs free energy of formation of organic molecules using the Joback group contribution method |

Python, REST |

Joback and Reid, 1987; Topping et al., 2016 |

|

Web GCM |

Estimates the standard Gibbs free energy of formation of organic molecules using the Mavrovouniotis group contribution method |

REST |

Jankowski et al., 2008 |

|

DNA |

||||

Promoters |

||||

Review |

Review of promoter prediction methods for Homo sapiens |

Pedersen et al., 1999 |

||

PePPER |

Predicts prokaryote promoters |

REST |

de Yong et al., 2012 |

|

Promoter |

Predicts vertebrate PolII promoters |

REST |

Knudsen, 1999 |

|

PromoterHunter |

Predicts prokaryote promoters |

REST |

Klucar et al., 2010 |

|

Genes |

||||

Review |

Review of several gene prediction software tools |

https://cmgm.stanford.edu/biochem218/Projects%202007/Mcelwain.pdf |

McElwain, 2007 |

|

GeneMark |

Family of tools for predicting viral, prokaryotic, archaeal, and eukaryotic genes |

Linux executable, REST |

Borodovsky and Lomsadze, 2011 |

|

GENESCAN |

Predicts plant and vertebrate genes |

Linux executable, REST |

Burge and Karlin, 1997 |

|

GLIMMER |

Predicts viral, prokaryotic, and archaeal genes |

C, REST |

Salzberg et al., 1998 |

|

Operons |

||||

Review |

Survey of several operon prediction methods |

Brouwer et al., 2008 |

||

DOOR |

Predicts prokaryotic operons |

REST |

Mao et al., 2014 |

|

OperonDB |

Estimates the likelihood that pairs of genes are in the same operon |

Perl, REST |

Ermolaeva et al., 2001 |

|

ProOpDB |

Predicts prokaryotic operons |

Java, REST |

Taboada et al., 2010 |

|

VIMSS |

Predicts prokaryotic and archaeal operons |

R, REST |

Price et al., 2005 |

|

Variant interpretation |

||||

PolyPhen-2 |

Predicts the functional effects of amino acid substitutions |

C, REST |

Adzhubei et al., 2013 |

|

PROVEAN |

Predicts the functional effects of amino acid substitutions and indels |

C++, REST |

Choi and Chan, 2015 |

|

SIFT |

Predicts the functional effects of amino acid indels |

C++, REST |

Hu and Ng, 2013 |

|

RNA |

||||

Splice sites |

||||

Review |

Review of methods for predicting splice sites |

Desmet et al., 2010 |

||

GeneSplicer |

Predicts eukaryotic splice sites |

Java |

Pertea et al., 2001 |

|

Human Splicing Finder |

Identify and predict mutations’ effect on human splicing motifs |

REST |

Desmet et al., 2009 |

|

NetGene2 |

Predicts splice sites in Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Homo sapiens |

REST |

Hebsgaard et al., 1996 |

|

NNSplice |

Predicts splice sites Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens |

REST |

Reese et al., 1997 |

|

Secondary structure |

||||

Review |

Review of methods for predicting RNA secondary structures |

Lorenz et al., 2016 |

||

Mfold |

Predicts RNA secondary structures |

C, REST |

Zuker, 2003 |

|

RNAstructure |

Predicts RNA and DNA secondary structures |

C++, Java |

Reuter and Mathews, 2010 |

|

ViennaRNA |

Predicts RNA secondary structures |

C, Perl, Python |

Lorenz et al., 2011 |

|

Open reading frame |

||||

ORF Finder |

Predicts open reading frames |

Linux executable, REST |

Rombel et al., 2002 |

|

ORF Investigator |

Predicts open reading frames |

Windows executable |

https://sites.google.com/site/dwivediplanet/ORF-Investigator |

Dhar and Kumar, 2012 |

ORFPredictor |

Predicts open reading frames from EST and cDNA sequences |

Perl, REST |

Min et al., 2005 |

|

Terminators |

||||

Review |

Review of prokaryotic transcription termination that cites several methods for predicting terminators. |

Peters et al., 2011 |

||

ARNold |

Predicts prokaryotic rho-independent terminators |

REST |

Gautheret D and Lambert A, 2001 |

|

FindTerm |

Predicts prokaryotic rho-independent terminators |

REST |

http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=findterm&group=programs&subgroup=gfindb |

Solovyev and Salamov, 2011 |

GeSTer |

Predicts prokaryotic rho-independent terminators |

REST |

Mitra et al., 2011 |

|

TransTermHP |

Predicts prokaryotic rho-independent terminators |

C++ |

Kingsford et al., 2007 |

|

Proteins |

||||

Localization |

||||

Review |

Review of methods for predicting the subcellular localization of prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins |

Imai and Nakai, 2010 |

||

Review |

Review of methods for predicting the subcellular localization of prokaryotic proteins |

Gardy and Brinkman, 2006 |

||

Cell-PLoc |

Predicts the subcellular localization of proteins for multiple species |

REST |

Chou and Shen, 2010 |

|

MultiLoc |

Predicts the subcellular localization of proteins for multiple species |

Python, REST |

Blum et al., 2009 |

|

PSORTb |

Predicts the subcellular localization of prokaryotic and archaeal proteins |

C++, Perl, REST |

Yu et al., 2010 |

|

SecretomeP |

Predicts signal peptide-independent protein secretion |

REST, tcsh |

Bendtsen et al., 2004 |

|

WoLF PSORT |

Predicts the subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins |

Perl, REST |

Horton et al., 2007 |

|

Signal sequence |

||||

Review |

Architecture, function and prediction of long signal peptides |

Hiss and Schneider, 2009 |

||

Phobius |

Predict protein transmembrane topology and signal peptides from AA sequences |

Java, REST |

Käll et al., 2007 |

|

PRED-LIPO |

Predict lipoprotein and secretory signal peptides in gram-positive bacteria |

REST |

Bagos et al., 2008 |

|

PRED-SIGNAL |

Predict signal peptides in archaea |

REST |

Bagos et al., 2009 |

|

SignalP |

Predict signal peptide cleavage sites in prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins |

Perl, REST |

Petersen et al., 2011 |

|

Disulfide bonds |

||||

Review |

Review of methods predicting disulfide bonds |

Tsai et al., 2007 |

||

Review |

Review of methods predicting disulfide bonds |

Márquez-Chamorro and Aguilar-Ruiz, 2015 |

||

Cyscon |

A consensus model for predicting disulfide bonds |

REST |

Yang et al., 2015 |

|

DIANNA |

Predicts disulfide bonds |

Python, REST |

Ferrè F and Clote P, 2006 |

|

Dinsolve |

Predicts disulfide bonds |

REST |

Yaseen and Li, 2013 |

|

DIPro |

Predicts disulfide bonds |

REST, Perl |

Cheng et al., 2006 |

|

DISULFIND |

Predicts disulfide bonds |

REST |

Ceroni et al., 2006 |

|

Complex abundance |

||||

SiComPre |

Predicts the abundances of Homo sapiens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein complexes |

C++, Java, Python |

Rizzetto et al., 2015 |

|

Half-lives |

||||

N-End rule |

Predicts the half-lives of Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian (rabit) proteins |

REST |

Bachmair et al., 1986 |

|

Interactions |

||||

miRNA targets |

||||

Review |

Review of methods for predicting miRNA targets |

Bartel, 2009 |

||

Review |

Review of methods for predicting miRNA targets |

Peterson et al., 2014 |

||

DIANA-microT-CDS |

Predicts miRNA targets in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens, and Mus musculus |

REST |

Reczko et al., 2012 |

|

miRSearch |

Predicts miRNA targets in Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, and Rattus norvegicus |

REST |

||

MirTarget |

Predicts miRNAs targets in several animals |

REST |

Wang, 2016 |

|

PITA |

Predicts miRNA targets in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens, and Mus musculus |

C, Perl, REST |

Kertesz et al., 2007 |

|

STarMir |

Predicts miRNA targets in Caenorhabditis elegans, Homo sapiens, and Mus musculus |

Perl, R, REST |

Lui et al., 2013 |

|

TargetScan |

Predicts miRNA targets in several animals |

Perl, REST |

Agarwal et al., 2015 |

|

Protein-DNA binding sites |

||||

Review |

Review of tools for predicting transcription factor binding sites |

Tompa et al., 2005 |

||

Review |

Review of tools for predicting transcription factor binding sites |

Jayaram et al., 2016 |

||

DBD |

Predicts DNA-binding domains of transcription factors |

REST |

Wilson et al., 2008 |

|

JASPAR |

Predicts transcription factor binding motifs |

Perl, Python, R, REST, Ruby |

Mathelier et al., 2016 |

|

Weeder |

Predicts likely transcription factor binding motifs |

C++, REST |

Pavesi et al., 2004 |

|

Chaperones |

||||

BiPPred |

Predicts the interactions of mammalian proteins with chaperone BiP |

REST |

Schneider et al., 2016 |

|

cleverSuite |

Predicts the interactions of Escherichia coli proteins with chaperone DnaK/GroEL |

REST |

Klus et al., 2014 |

|

LIMBO |

Predicts the interactions of Escherichia coli proteins with chaperone DnaK |

REST |

Van Durme et al., 2009 |

|

Reaction center and atom mapping |

||||

Review |

Review of methods for reaction mapping and reaction center detection |

Chen et al., 2013 |

||

CAM |

Predicts the mapping of reactant to product atoms |

C++ |

Mann et al., 2014 |

|

CLCA |

Predicts the mapping of reactant to product atoms |

REST |

Kumar and Maranas, 2014 |

|

MWED |

Predicts the mapping of reactant to product atoms |

Lisp |

Latendresse et al., 2012 |

|

ReactionDecoder |

Predicts the mapping of reactant to product atoms |

Java |

Rahman et al., 2016 |

|

ReactionMap |

Predicts the mapping of reactant to product atoms |

REST |

Fooshee et al., 2013 |

1.4.2. Modeling and simulation tools¶

Here, we review several advances in modeling and simulation technology that we believe are beginning to enable researchers to aggregate and organize the data needed for WC modeling and design, describe, simulate, calibrate, verify, and analyze WC models.

1.4.2.1. Data aggregation and organization tools¶

To make the large amount of publicly available data usable for modeling, researchers are developing tools such as BioServices [54] for programmatically accessing repositories and using PGDBs to organize the data needed for modeling. PGDBs are well-suited to organizing the data needed for WC models because they support structured representations of metabolites, DNA, RNA, proteins, and their interactions. However, traditional PGDBs provided limited support for non-metabolic pathways and quantitative data. Consequently, we are developing WholeCellKB, a PGDB specifically designed for WC modeling [30].

1.4.2.2. Model design tools¶

Several software tools have been developed for designing models of individual cellular pathways including BioUML [67], CellDesigner [68], COPASI [69], JDesigner [70], and Virtual Cell [71] which support dynamical modeling; RuleBender which supports rule-based modeling [72]; and COBRApy [73], FAME [74], and RAVEN [75] which support constraint-based metabolic modeling; and (Table 1.4).

Recently, researchers have developed several tools that support some of the features needed for WC modeling. This includes SEEK which helps researchers design models from data tables [76], Virtual Cell which helps researchers design models from KEGG pathways [71][56], MetaFlux which helps researchers design metabolic models from PGDBs [61], the Cell Collective [77] and JWS Online [78] which help researchers build models collaboratively, PySB which helps researchers design models programmatically [79], and semanticSBML [80] and SemGen [81] which help researchers merge models.

Tool |

URL |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

Data aggregation tools |

||

BioCatalogue |

Bhagat et al., 2010 |

|

BIOSERVICES |

Cokelaer et al., 2013 |

|

Data organization tools |

||

GMOD |

Papanicolaou and Heckel, 2010 |

|

Pathway Tools |

Karp et al., 2016 |

|

WholeCellKB |

Karr et al., 2013 |

|

Model design tools |

||

CellDesigner |

Matsuoka et al., 2014 |

|

COPASI |

Mendes et al., 2009 |

|

JWS Online |

Olivier and Snoep, 2004 |

|

MetaFlux |

Latendresse et al., 2012 |

|

PhysioDesigner |

Asai et al., 2012 |

|

RAVEN |

Agren et al., 2013 |

|

RuleBender |

Smith et al., 2012 |

|

VirtualCell |

Schaff et al., 2016 |

|

Model testing and verification tools |

||

biolab |

Clarke at al., 2008 |

|

MEMOTE |

||

SBML-to-PRISM |

||

Model description languages |

||

BioNetGen |

Harris et al., 2016 |

|

BioPAX |

Demir et al., 2010 |

|

CellML |

Cuellar et al., 2015 |

|

kappa |

Wilson-Kanamori et al., 2015 |

|

ML-Rules |

Maus et al., 2011 |

|

PySB |

Lopez et al., 2013 |

|

SBML |

Hucka et al., 2015 |

|

Simulation description languages |

||

SED-ML |

Waltemath et al., 2011 |

|

SESSL |

Ewald and Uhrmacher, 2014 |

|

Simulators |

||

cobrapy |

Ebrahim et al., 2013 |

|

COPASI |

Mendes et al., 2009 |

|

ECell |

Takahashi et al., 2003 |

|

Lattice Microbes |

Hallock et al., 2014 |

|

libRoadRunner |

Somogyi et al., 2015 |

|

NFSim |

Sneddon et al., 2011 |

|

VirtualCell |

Schaff et al., 2016 |

|

Simulation result formats |

||

HDF5 |

Folk et al., 2011 |

|

NuML |

Dada et al., 2017 |

|

SBRML |

Dada et al., 2010 |

|

Simulation result databases |

||

Bookshelf |

Vohra et al., 2010 |

|

Dynameomics |

van der Kamp et al., 2010 |

|

SEEK |

Wolstencroft et al., 2011 |

|

WholeCellSimDB |

Karr et al., 2014 |

|

Visualization tools |

||

Vega |

Satyanarayan et al., 2017 |

|

The Visualization Toolkit (VTK) |

Hanwell et al., 2015 |

|

WholeCellViz |

Lee et al., 2013 |

|

Workflow management tools |

||

Galaxy |

Walker et al., 2016 |

|

Taverna |

Wolstencroft et al., 2013 |

|

VizTrails |

Freire and Silva, 2012 |

|

However, none of these tools are well-suited to WC modeling because none of these tools support all of the features needed for WC modeling including programmatically designing models from large data sources such as PGDBs; collaboratively designing models over a web-based interface; designing composite, multi-algorithmic models; representing models in terms of rule patterns; and recording the data sources and assumptions used to build models.

1.4.2.3. Model selection tools¶

Several methods have also been developed to help researchers select among multiple potential models, including likelihood-based, Bayesian, and heuristic methods [82]. ABC-SysBio [83][84], ModelMage [85], and SYSBIONS [86] are some of the most advanced model selection tools. However, these tools only support deterministic dynamical models.

1.4.2.4. Model refinement tools¶

Several tools have been developed for refining models, including using physiological data to identify molecular gaps in metabolic models and using databases of molecular mechanisms to fill molecular gaps in metabolic models [87][88]. GapFind uses mixed integer linear programming to identify all of the metabolites that cannot be both produced and consumed in metabolic models, one type of molecular gap in metabolic models [89]. GapFill [89], OMNI [90], and SMILEY [91] use linear programming to identify the most parsimonious set of reactions from reaction databases such as KEGG [56] to fill molecular gaps in metabolic models. FastGapFill is one of the most efficient of these gap filling tools [92]. GrowMatch extends gap filling to find the most parsimonious set of reactions that not only fill molecular gaps in metabolic models, but also correct erroneous gene essentiality predictions [93]. ADOMETA [94], GAUGE [95], likelihood-based gap filling [96], MIRAGE [97], PathoLogic [98] and SEED [99] extend gap filling further by using sequence homology and other genomic data to identify the genes which most likely catalyze missing reactions in metabolic networks. However, these tools are only applicable to metabolic models.

1.4.2.5. Model formats¶

Several formats have been developed to represent cell models including formats such as CellML [100] that represent models as collections of variables and equations, formats such as SBML [101] that represent models as collections of species and reactions, and more abstract formats such as BioNetGen [102], Kappa [103], and ML-Rules [104] that represent models as collections of species and rule patterns.

The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) was developed in 2002 to represent dynamical models that can be simulated by integrating ordinary differential equations or using the stochastic simulation algorithm, as well as the semantic biological meaning of models. Recently, SBML has been extended to support a wide range of models through the development of several new packages. The flux balance constraints package supports constraint-based models, the qualitative models package supports logical models, the spatial processes package support spatial models that can be simulated by integrating PDEs, the multistate multicomponent species package supports rule-based model descriptions, and the hierarchical model composition package supports composite models. SBML is by far the most widely supported and commonly used format for representing cell models. For example, SBML is supported by COPASI [69], the most commonly used cell modeling software program and BioModels, the most commonly used cell model repository [105]. However, SBML creates verbose model descriptions, the multistate multicomponent species package only supports a few types of combinatorial complexity, SBML does not directly support multi-algorithmic models, and SBML cannot represent model provenance including the data sources and assumptions used to build models [106].

More recently, Faeder and others have developed BioNetGen [102] and other rule-based formats to efficiently describe the combinatorial complexity of protein-protein interactions. These formats enable researchers to describe models in terms of species and reaction patterns which can be evaluated to generate all of the individual species and reactions in a model. This abstraction helps researchers describe reactions directly in terms of their chemistry, describe large models concisely, and avoid errors in enumerating species and reactions. Models that are described in rule-based formats such as BioNetGen can be simulated either by enumerating all of the possible species and reactions and then simulating the expanded model via conventional deterministic or stochastic dynamical simulation methods, or via network-free simulation which iteratively discovers individual species and reactions during simulation [107]. BioNetGen is the most commonly used rule-based modeling format and NFsim is the most commonly used network-free simulator. However, BioNetGen only supports few types of combinatorial complexity, BioNetGen does not support composite or multi-algorithmic models, BioNetGen cannot represent the semantic biological meaning of models, and BioNetGen cannot represent model provenance.

1.4.2.6. Simulation algorithms¶

Several algorithms have been developed to simulate cells with a wide range of granularity including algorithms for integrating systems of ODEs and PDEs, stochastic simulation algorithms, algorithms for simulating logical networks and Petri nets, and hybrid algorithms for co-simulating models that are composed of mathematically-dissimilar submodels.

The most commonly used algorithms to simulate cell models include algorithms for integrating systems of ODEs. These algorithms are best suited to simulating well-characterized and well-mixed systems that involve large concentrations that are robust to stochastic fluctuations. These algorithms are poorly suited to simulating stochastic processes that involve small concentrations, as well as poorly characterized pathways with little kinetic data. Consequently, ODE integration algorithms are poorly suited for WC modeling.

Stochastic simulation algorithms such as the Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA) or Gillespie’s Algorithm [108], newer, more efficient implementations of SSA such as the Gibson-Bruck method and RSSA-CR [109], and approximations of SSA such as tau leaping, are commonly used to simulate pathways that involve small concentrations that are susceptible stochastic variation. However, these algorithms are only suitable for dynamical models which require substantial kinetic data, they are computationally expensive, especially for models that include reactions that have high fluxes, and they are limited to models with small state spaces. Consequently, stochastic simulation algorithms are poorly suited for simulating WC models.

Network-free simulation algorithms are stochastic simulation algorithms for efficiently simulating rule-based models without enumerating every possible species and reaction prior to simulation and instead discovering the active species and reactions during simulation. Unlike traditional stochastic simulation algorithms, network-free simulation algorithms can represent large models that have combinatorially large or even infinite state spaces. Otherwise, network-free stochastic simulation algorithms have the same limitations as other stochastic simulation algorithms.

FBA is the second-most commonly used algorithm for simulating cell models. FBA predicts the steady-state flux of each metabolic reaction using detailed information about the stoichiometry and catalysis of each reaction, a small amount of quantitative data about the chemical composition of cells, a small amount of data about the exchange rate of each extracellular nutrient, and the assumption that metabolism has evolved to maximize the rate of cellular growth. However, FBA has limited ability to predict metabolite concentrations and temporal dynamics, and its assumptions are largely only applicable to microbial metabolism. Consequently, FBA is not well-suited to simulating entire cells.

Logical simulation algorithms are frequently used for coarse-grained simulations of transcriptional regulation and other pathways for which we have limited kinetic data. Logical simulations are computationally efficient because they are coarse-grained. However, logical simulation algorithms are poorly suited to WC modeling because they cannot generate detailed quantitative predictions, and therefore have limited utility for medicine and bioengineering.

Multi-algorithmic simulations are ideal for WC modeling because they can simulate models that include fine-grained representations of well-characterized pathways, as well as coarse-grained representations of poorly-characterized pathways. Takahashi et al. developed one of the first algorithms for co-simulating multiple mathematically-dissimilar submodels [3]. However, their algorithm is not well-suited to WC modeling because it does not support FBA or network-free simulation. Recently, we and others developed a multi-algorithm simulation meta-algorithm which supports ODE integration, conventional stochastic simulation, network-free stochastic simulation, FBA, and logical simulation [27]. However, our algorithm violates the arrow of time and is not scalable to large models.

1.4.2.7. Simulation experiment formats¶

The Minimum Information About a Simulation Experiment (MIASE) guidelines have been developed to establish the minimum metadata that should be provided about a simulation experiment to enable other researchers to reproduce and understand the simulation [2]. The Simulation Experiment Description Markup Language (SED-ML) [110] and the Simulation Experiment Specification via a Scala Layer (SESSL) [111] formats have been developed to represent simulation experiments. Both formats are capable of representing all of the model parameters and simulator arguments needed to simulate a model. However, both formats are limited to a small range of model formats and simulators. SED-ML is limited to models that are represented using XML-based formats such as SBML, and SESSL is currently limited to Java-based simulators. Consequently, neither is currently well-suited to WC modeling.

1.4.2.8. Simulation tools¶

Numerous tools have been developed to simulate cell models including the BioUML [67], Cell Collective [77], COBRApy [73], COPASI [69], E-Cell [112], FAME [74], iBioSim [113], libRoadRunner [114], JWS Online [78], NFsim [107], RAVEN [75], and Virtual Cell [71].

COPASI is the most commonly used simulation tool. COPASI supports several deterministic, stochastic, and hybrid deterministic/stochastic simulation algorithms. However, COPASI does not support network-free stochastic simulation, FBA, logical, or multi-algorithmic simulation and COPASI does not support high-performance parallel simulation of large models.

Virtual Cell supports several deterministic, stochastic, hybrid deterministic/stochastic, network-free, and spatial simulation algorithms. However, Virtual Cell does not support FBA or multi-algorithmic simulations and Virtual Cell does not support high-performance parallel simulation of large models.

COBRApy, FAME, and RAVEN support FBA of metabolic models. However, these packages provide no support for other types of models.

E-Cell is one of the only simulation programs that supports multi-algorithmic simulation. However, E-Cell does not support FBA or rule-based simulation, and E-Cell does not scale well to large models.

Several tools including cupSODA [115], cuTauLeaping [116], and Rensselaer’s Optimistic Simulation System (ROSS) [117] have been developed to simulate models in parallel. However, cupSODA only supports deterministic simulation, cuTauLeaping only supports network-based stochastic simulation, cupSODA and cuTauLeaping only support GPUs, and ROSS is a low-level, general-purpose framework for distributed CPU simulation.

1.4.2.9. Calibration tools¶

Accurate parameter values are essential for reliable predictions. Many methods have been developed to calibrate models by numerically optimizing the values of their parameters, including derivative-based initial value methods and stochastic multiple shooting methods [118].

Several complementary methods have also been developed to optimize computationally-expensive, high-dimensional functions, including surrogate modeling, distributed optimization, and automatic differentiation. Surrogate modeling, which is also referred to as function approximation, metamodeling, response surface modeling, and model emulation, promises to reduce the computational cost of numerical optimization by optimizing a computationally cheaper model which approximates the original model [119][120][121][122]. Surrogate modeling has been used in several fields including aerospace engineering [123], hydrology [124], and petroleum engineering [125]. However, further work is needed to develop methods for efficiently generating reduced surrogate WC models.

Distributed optimization is also a promising approach for optimizing computationally expensive functions. Distributed optimization uses multiple agents, each simultaneously employing the same algorithm on different regions, to quickly identify optima [126][127]. Furthermore, agents can cooperate by exchanging information. Distributed optimization has been used in several fields including aerospace and electrical engineering [128][129] and molecular dynamics [130].

Another promising approach for optimizing computationally expensive functions is automatic differentiation. Automatic differentiation is an efficient technique for analytically computing the derivative of a function [131]. Automatic differentiation can be used to make derivative-based optimization methods tractable in cases where finite difference calculations are prohibitively expensive. Automatic differentiation has been used to identify parameters in chemical engineering [132], biomechanics [133], and physiology [134].

Several software tools have also been developed for calibrating cell models [135][136][137][138][139]. Some of the most advanced model calibration tools include DAISY which can evaluate the identifiability of a model [140], ABC-SysBio which uses approximate Bayesian computation [83], saCeSS which supports distributed, collaborative optimization [141], and SBSI which supports several distributed optimization methods [142]. Some of the most popular modeling tools, including COPASI [69] and Virtual Cell [71], also provide model calibration tools. However, none of these tools support multi-algorithmic models. To efficiently calibrate WC models, we should combine numerical optimization methods with additional techniques such as reduced surrogate modeling, distributed computing, and automatic differentiation.

1.4.2.10. Verification tools¶

Several tools have been developed to verify cell models, including formal verification tools that seek to prove or refute mathematical properties of models and informal verification tools that help modelers organize and evaluate computational tests of models. BioLab [143] and PRISM [144] are formal tools for verifying BioNetGen-encoded and SBML-encoded models, respectively. Memote [145] and SciUnit [146] are unit testing frameworks for organizing computational tests of models. Continuous integration tools such as CircleCI [147] and Jenkins [148] can be used to regularly verify models each time they are modified and pushed to a version control system (VCS) such as Git [149].

1.4.2.11. Simulation results formats¶

HDF5 is an ideal format for storing simulation results [150]. In particular, HDF5 supports hierarchical data structures, HDF5 supports compression, HDF5 supports chunking to facilitate fast retrieval of small slices of large datasets, HDF5 can store both simulation results and their metadata, and there are HDF5 libraries available for several languages including C++, Java, MATLAB, Python, and R.

1.4.2.12. Simulation results databases¶

Several database systems have been developed to organize simulation results for visual and mathematical analysis and disseminate simulation results to the community [151][152][153][154][155][156][157]. We developed WholeCellSimDB, a hybrid relational/HDF5 database, to organize, search, and share WC simulation results [158]. WholeCellSimDB uses HDF5 to store simulation results and a relational database to store their metadata. This enables WholeCellSimDB to efficiently store simulation results, quickly search simulations by their metadata, and quickly retrieve slices of simulation results. WholeCellSimDB providers uses two interfaces to deposit simulation results; a web-based interface to search, browse, and visualize simulation results; and a JSON web service to retrieve simulation results. However, further work is needed to scale WholeCellSimDB to larger models and to develop tools for quickly searching WholeCellSimDB.

1.4.2.13. Simulation results analysis¶